Bacterial Skin Infections: Impetigo, Cellulitis, and Antibiotics Explained

When your child comes home from school with red, crusty sores around the nose, or you wake up with a swollen, painful patch of skin on your leg, it’s easy to assume it’s just a rash or a bug bite. But these could be signs of something more serious: bacterial skin infections. Two of the most common are impetigo and cellulitis - and they’re not the same. One is contagious and mostly affects kids. The other can turn dangerous fast, especially in adults. And the antibiotics you reach for? They might not work at all if you pick the wrong one.

What Is Impetigo - And Why It’s More Common Than You Think

Impetigo is the most common bacterial skin infection in children, especially between ages 2 and 5. It’s often called ‘school sores’ because it spreads quickly in daycare centers and classrooms. You’ll see small red bumps or blisters, usually around the nose and mouth. Within a few days, they burst, ooze, and form that unmistakable honey-colored crust. It doesn’t usually hurt, but it itches - and that’s how it spreads. The real surprise? It’s not mostly caused by strep anymore. For decades, doctors thought Group A Streptococcus was the main culprit. Now, we know over 90% of cases are caused by Staphylococcus aureus, often mixed with strep. And here’s the kicker: nearly all these staph strains make an enzyme called penicillinase, which destroys penicillin. That means if you’re given penicillin or amoxicillin, there’s a 68% chance it won’t work. There are two types. Nonbullous impetigo (the most common) looks like those crusty sores. Bullous impetigo, seen mostly in babies under 2, causes larger fluid-filled blisters that burst and leave behind a ring-like edge. In rare cases, it can turn into ecthyma - a deeper ulcer that scars. Even rarer is staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), where the skin peels off like a burn. It’s life-threatening in infants and needs emergency care.Cellulitis: When the Infection Goes Deeper

Cellulitis isn’t just a skin rash. It’s an infection that spreads into the deeper layers - the dermis and fat underneath. It looks like a red, swollen, warm area that keeps growing. The edges are blurry, not sharp. It’s often on the lower legs, but can show up anywhere. Unlike impetigo, it’s not contagious. You don’t catch it from someone else. You get it when bacteria slip in through a cut, scrape, insect bite, or even a crack in the skin from athlete’s foot. The main bacteria? Streptococcus pyogenes - the same one linked to strep throat - causes 60-80% of cases. Staph aureus is behind 20-30%. But here’s the danger: cellulitis can turn into sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis (flesh-eating disease), or spread to the bloodstream. About 5-9% of adults with cellulitis end up with bacteremia. If you’re over 65, diabetic, or have swollen legs from poor circulation, your risk jumps. People with diabetes are 3.2 times more likely to get it. Obesity raises it by 2.7 times. It doesn’t just hurt - it can make you feel sick. Fever, chills, and feeling generally unwell are red flags. If the red area grows more than 2 cm in a day, or you develop a fever over 101°F, you need help fast.Antibiotics: Why One Size Doesn’t Fit All

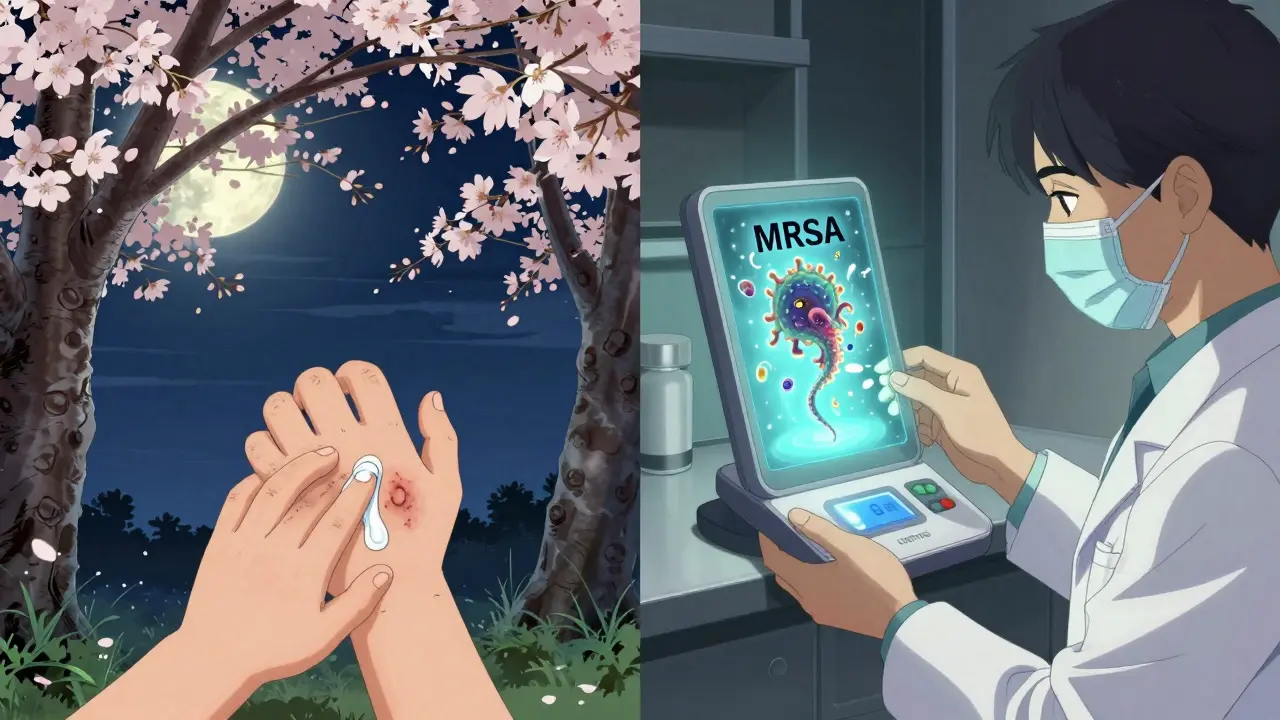

You can’t treat impetigo and cellulitis the same way. It’s not about strength - it’s about depth and type. For mild, localized impetigo, topical mupirocin (Bactroban) is the gold standard. Apply it three times a day for five days. Clean the area first with warm soapy water and gently remove the crusts. Studies show it cures 92% of cases. It’s safe for kids, doesn’t cause resistance like oral antibiotics, and keeps the infection from spreading. But if the infection is widespread, bullous, or doesn’t improve in 3 days, you need oral antibiotics. Cephalexin (Keflex) is commonly used - 25 to 50 mg per kg of body weight, split into doses, for 7 days. For kids with SSSS or severe cases, hospitalization and IV antibiotics like clindamycin or vancomycin may be needed. Cellulitis? Topical creams won’t cut it. The infection is too deep. You need antibiotics that get into the bloodstream. For mild cases in healthy adults, oral cephalexin or dicloxacillin (500 mg four times a day) for 5 to 14 days works. But if you’re allergic to penicillin, alternatives like doxycycline or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) are used. Here’s the big shift: methicillin-resistant Staph aureus (MRSA) is now in half of all community skin infections in the U.S. That means traditional antibiotics like cephalexin might fail. If you live in an area with high MRSA rates - or if the infection isn’t improving after 48 hours - your doctor should switch to doxycycline or Bactrim. These target MRSA and have cure rates of 85-90%.

What Happens If You Wait Too Long

Impetigo usually clears up without scars. But there’s a hidden risk: post-streptococcal acute glomerulonephritis (AGN). That’s a kidney problem that can develop 1-3 weeks after a strep infection, even if the skin sores are gone. It’s rare - only 1-5% of cases - but it can lead to high blood pressure and kidney damage. That’s why treating strep-related impetigo matters, even if it looks mild. Cellulitis is a different beast. Left untreated, it can spread to the blood, bones, or joints. Necrotizing fasciitis - though rare - kills 1 in 5 people who get it. The CDC reports 2.3 million emergency room visits for cellulitis each year in the U.S. alone. And it’s not just adults. Kids with underlying conditions like eczema or immune problems are at higher risk. The bottom line? Don’t wait. If you see spreading redness, fever, or pain that’s getting worse, don’t call your doctor tomorrow - call today.Prevention: Simple Steps That Make a Big Difference

You can’t always avoid bacteria, but you can stop them from taking hold. For impetigo: Wash hands often. Don’t share towels, clothing, or bedding. Keep fingernails short to prevent scratching. During outbreaks, use antibacterial soap for daily washing. Kids should stay home from school or daycare until 24 hours after starting antibiotics - or until the sores are dry and crusted. For cellulitis: Treat cuts and scrapes right away. Clean with soap and water, cover with a bandage. If you have diabetes or poor circulation, check your feet daily. Treat athlete’s foot - even if it doesn’t itch - because cracked skin is a doorway for bacteria. Moisturize dry skin. Wear protective footwear. Don’t ignore insect bites or rashes that don’t heal. And avoid squeezing pimples or picking at scabs. That’s how staph gets in.

What’s Changing in Treatment - And What’s Coming

Antibiotic resistance is making old treatments obsolete. In 2024, a new topical treatment called retapamulin (Altabax) showed 94% effectiveness in pediatric impetigo trials. It’s not yet first-line everywhere, but it’s an option when mupirocin fails. The bigger shift is in diagnostics. Right now, doctors guess the bug based on how it looks. But new point-of-care tests - still in trials - can identify the exact bacteria and its resistance pattern in under 30 minutes. The NIH is funding $12.5 million to bring these to clinics by 2027. That means no more trial-and-error antibiotics. You get the right drug, the first time. The American Academy of Dermatology is pushing hard to cut unnecessary antibiotic use by 30% by 2025. Why? Because overuse breeds resistance. Mild rashes that look like impetigo might be fungal or viral. And not every red patch is cellulitis - it could be a blood clot or eczema flare-up. Getting the diagnosis right matters more than ever.When to See a Doctor - And When to Call 911

See a doctor if:- Sores spread despite cleaning and over-the-counter care

- Redness on the leg grows quickly or becomes painful

- You have a fever with a skin rash

- Diabetes or weakened immune system + any skin wound that won’t heal

- Skin looks burned or is peeling off in large sheets

- High fever with severe pain and swelling

- Red streaks spreading from the infected area

- Confusion, dizziness, or rapid heartbeat with skin symptoms

Is impetigo contagious?

Yes, impetigo is highly contagious. It spreads through direct skin contact or by touching items like towels, toys, or bedding that have been contaminated. Children in daycare or school settings are most at risk. After 24 hours of starting the right antibiotic, the infection is no longer contagious.

Can cellulitis spread from person to person?

No, cellulitis is not contagious. You can’t catch it from someone else. It happens when bacteria enter your own skin through a cut, bite, or crack. Even if someone has cellulitis, you won’t get it from touching them - unless you have an open wound and come into contact with their infected fluid.

Why doesn’t penicillin work for impetigo anymore?

Most staph bacteria that cause impetigo now produce an enzyme called penicillinase, which breaks down penicillin before it can kill the bacteria. Studies show up to 68% of cases won’t respond to penicillin or amoxicillin. That’s why doctors now use mupirocin, cephalexin, or other antibiotics that aren’t affected by this enzyme.

What’s the difference between impetigo and MRSA?

Impetigo is a type of skin infection, often caused by staph or strep. MRSA is a specific type of staph bacteria that’s resistant to certain antibiotics, including methicillin. Many cases of impetigo today are caused by MRSA, especially in areas with high resistance rates. So MRSA can cause impetigo - but not all impetigo is MRSA.

How long does it take for antibiotics to work on cellulitis?

Most people start to feel better within 48 to 72 hours after starting oral antibiotics. The redness and swelling should begin to shrink. If there’s no improvement after 3 days, or if symptoms worsen, you need to go back to your doctor - you might need stronger antibiotics or IV treatment.

Can you treat impetigo without antibiotics?

Mild cases may heal on their own in 2-3 weeks, but they remain contagious and can spread to others or cause complications like kidney problems. Antibiotics speed up healing, reduce transmission, and lower the risk of post-infection issues. For children, especially, treatment is strongly recommended.

Are there natural remedies for bacterial skin infections?

Some people use honey, tea tree oil, or coconut oil on minor skin irritations, but there’s no strong evidence they work against impetigo or cellulitis. These infections require targeted antibiotics. Relying on natural remedies can delay proper treatment and allow the infection to worsen - especially in children or people with health conditions.

Hilary Miller

January 22, 2026 AT 08:00Malik Ronquillo

January 24, 2026 AT 05:36Lana Kabulova

January 25, 2026 AT 20:22Rob Sims

January 26, 2026 AT 18:22arun mehta

January 28, 2026 AT 02:09Lauren Wall

January 28, 2026 AT 22:56Oren Prettyman

January 29, 2026 AT 14:45Tatiana Bandurina

January 30, 2026 AT 19:28Philip House

January 31, 2026 AT 05:52Ryan Riesterer

February 1, 2026 AT 17:34Jasmine Bryant

February 2, 2026 AT 12:19Liberty C

February 4, 2026 AT 05:08shivani acharya

February 5, 2026 AT 14:16Sarvesh CK

February 6, 2026 AT 16:48