Drug Shortage Predictions: Forecasting Future Scarcity in 2025-2030

By 2026, nearly one in three commonly prescribed generic drugs in the U.S. could face shortages. That’s not a worst-case scenario-it’s what experts are already seeing on the ground. Hospitals are rationing insulin. Oncology clinics are switching to less effective alternatives. Parents are scrambling to find pediatric antibiotics. This isn’t just bad luck. It’s a predictable collapse, and we’ve been warned for years.

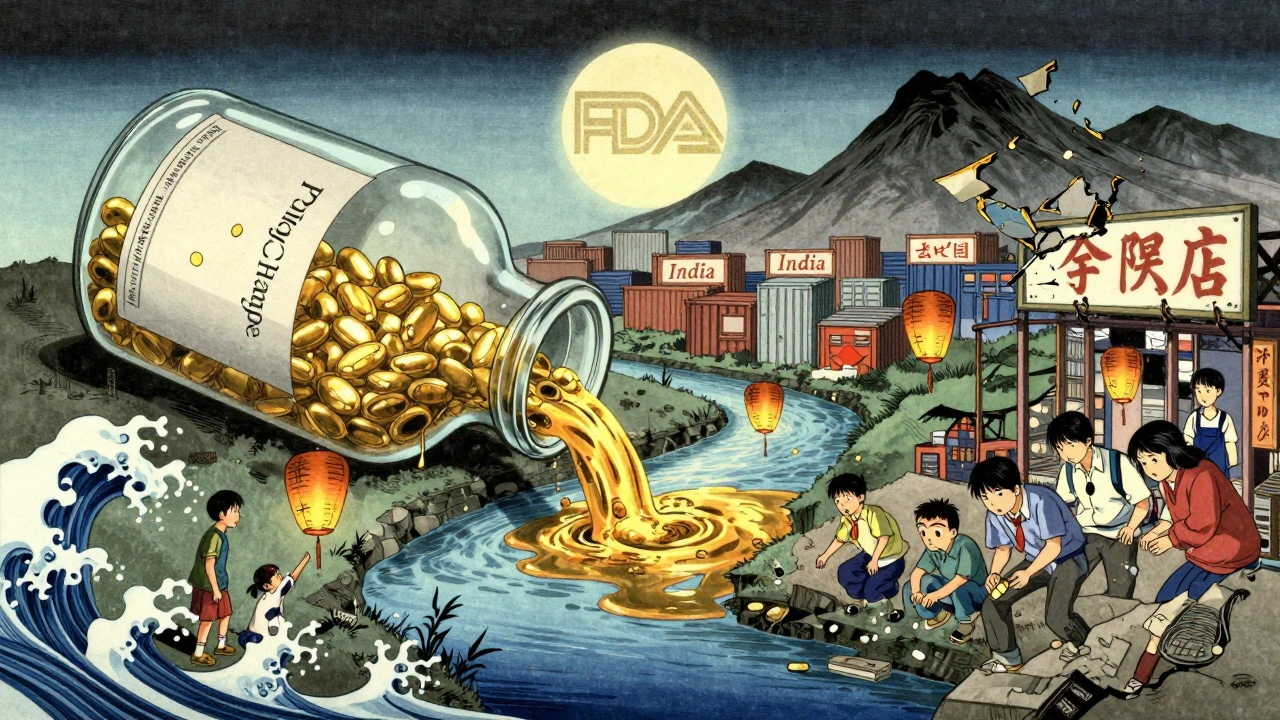

Why Drug Shortages Are Getting Worse

Drug shortages aren’t random. They follow patterns. And those patterns are getting sharper. The main drivers? Manufacturing failures, raw material shortages, and economic pressure on generic drug makers.

Over 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) used in U.S. medicines come from just two countries: India and China. When a single plant in Hyderabad or Shanghai shuts down for regulatory issues-like the 2024 FDA shutdown of a major API facility in Bengaluru-dozens of drugs vanish overnight. That’s not a glitch. It’s systemic.

Generic drug manufacturers operate on razor-thin margins. A vial of generic epinephrine might sell for $1.20. The cost to make it? $0.90. When shipping costs rise, energy prices spike, or labor gets tighter, there’s no room to absorb it. So they stop making it. And no one else steps in because the profit isn’t there.

The Forecast: What’s Coming by 2030

According to the FDA’s 2025 Drug Shortage Report, 218 drugs were in shortage last year. That’s up 37% from 2020. Projections show this number could hit 350 by 2028. But it’s not just about quantity-it’s about criticality.

Here’s what’s at risk:

- Chemotherapy drugs like vincristine and doxorubicin-used in 70% of pediatric cancer cases-could face 4+ month delays by 2027.

- Insulin production is concentrated in just three global facilities. Any disruption there means millions of diabetics go without.

- Anesthetics like propofol and ketamine are already in short supply. Hospitals are delaying surgeries because they can’t guarantee safe sedation.

- Antibiotics like ampicillin and cefazolin are vanishing in rural clinics. Doctors are forced to use broader-spectrum drugs, accelerating resistance.

Climate change adds another layer. Floods in India’s pharmaceutical belt in 2023 disrupted supply chains for six months. Droughts in Mexico cut water supply to drug manufacturing plants. These aren’t one-offs-they’re becoming the new normal.

Who’s Responsible? It’s Not Just One Culprit

Blaming manufacturers is easy. But the real problem is a web of policy, economics, and global dependency.

The FDA approves new drug facilities slowly. The average time to get a new API plant certified? 3.2 years. Meanwhile, companies that do get approved are often bought out by big pharma and shut down to reduce competition.

And then there’s the pricing system. Medicare pays for generic drugs based on the lowest price available. That sounds fair-until you realize it means no one can charge enough to invest in backup production, quality control, or redundancy. The system punishes preparedness.

Even the supply chain is fragile. One company makes 90% of the sterile vials used for injectables. That company is based in a region prone to earthquakes. No one has a Plan B.

Real-World Impact: Stories from the Front Lines

In a hospital in Milwaukee, a nurse told me they had to use a less effective antibiotic for a newborn with sepsis because the preferred drug was out. The baby survived-but the parents were terrified. That’s not a statistical outlier. It’s happening in 40% of U.S. hospitals right now.

On Reddit, a nurse in Arizona wrote: "We’ve had to delay chemo for three patients this month because we can’t get the drug. One of them is 12. We told her we’re trying. She asked if she was going to die. I didn’t know what to say."

These aren’t rare stories. They’re the new routine.

What’s Being Done? (And Why It’s Not Enough)

The U.S. passed the Drug Supply Chain Security Act in 2013. It was supposed to track drugs from factory to pharmacy. It did-but only for traceability, not for resilience. No one is required to stockpile backup supplies.

The FDA now has a Drug Shortage Task Force. They publish lists. They notify hospitals. But they can’t force a company to make more. And they don’t have the power to subsidize production.

Some states are trying. New York and California have started emergency stockpiles of critical drugs. But these are temporary fixes. They don’t solve the broken economics.

The World Health Organization has called for a global pharmaceutical reserve. But no country has committed funding. The U.S. spends $1.2 trillion a year on healthcare-but less than $50 million on securing the supply chain for essential drugs.

What You Can Do-And What Needs to Change

As a patient, you can’t fix the system alone. But you can push for change.

- Ask your pharmacist: "Is there a generic alternative? Is it in stock?"

- Report shortages to the FDA’s Drug Shortage Portal. Every report matters.

- Support advocacy groups like the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists-they’re pushing for mandatory buffer stocks.

But real change needs policy:

- Subsidize backup production for essential drugs-like we do for vaccines.

- Require multi-sourcing for critical medications. No drug should rely on one factory.

- Reform pricing so manufacturers can profit without exploiting patients.

- Invest in domestic API manufacturing with tax incentives and fast-track approvals.

The technology exists. The data is clear. We know exactly which drugs will run out, when, and why. We just haven’t acted like it’s an emergency.

The Bottom Line

Drug shortages aren’t going away. They’re getting worse. And they’re not just about pills and vials-they’re about lives. A child with cancer. An elderly person with diabetes. A mother with an infection.

By 2030, we could be looking at a world where basic medicines are treated like luxury goods-available only to those who can pay, or who live near a well-stocked hospital. That’s not progress. That’s failure.

We have the tools to prevent this. We just need the will.

Why are generic drugs so often in short supply?

Generic drugs have very low profit margins, so manufacturers stop making them when costs rise-even slightly. Most are made in just one or two overseas factories. If one shuts down, there’s no backup. The U.S. pricing system rewards the cheapest option, which discourages investment in reliable production.

Which drugs are most likely to run out by 2027?

Cancer drugs like vincristine and doxorubicin, insulin, anesthetics like propofol, and antibiotics like ampicillin and cefazolin are at highest risk. These are all made in concentrated facilities with little redundancy. The FDA tracks these in its priority shortage list, and the number of critical drugs in shortage has doubled since 2020.

Can the FDA fix drug shortages?

The FDA can warn about shortages and speed up inspections, but it can’t force companies to make more drugs. It doesn’t control pricing, manufacturing capacity, or global supply chains. Its role is reactive, not preventive. Real fixes require Congress to change economic incentives and fund backup production.

Is this problem happening outside the U.S.?

Yes. The WHO reports that low- and middle-income countries face even worse shortages because they rely entirely on imports and have no stockpiles. In parts of Africa and Southeast Asia, shortages of antibiotics and insulin are routine. The problem is global-but the U.S. has the resources to lead a solution.

How can I find out if my medication is in short supply?

Check the FDA’s Drug Shortages page, which is updated weekly. You can also ask your pharmacist directly-they’re required to report shortages. Some hospitals and pharmacy chains have internal alerts. If your drug is suddenly unavailable, ask if there’s an alternative-and if not, contact your doctor immediately.

Are brand-name drugs safer from shortages?

Not necessarily. While brand-name drugs often have more profit margin to buffer disruptions, many rely on the same generic APIs and packaging. For example, the brand-name version of a chemotherapy drug may use the same vial and active ingredient as the generic. So if the API plant shuts down, both versions are affected.

What’s Next?

If nothing changes, drug shortages will become part of everyday life-like delayed flights or crowded emergency rooms. But unlike those, drug shortages can kill.

The next five years will decide whether we treat medicine as a human right-or a commodity subject to market whim. The data is clear. The solutions exist. What’s missing is the political will.

Don’t wait for a crisis. Ask questions. Demand action. Your life-and the lives of people you love-depend on it.

Kurt Russell

December 7, 2025 AT 12:49This isn't just a healthcare crisis-it's a national security issue. Imagine a war where the enemy doesn't need bullets, just a power outage in Hyderabad. We're one bad monsoon away from mass casualties. We've been warned since 2015, and still we treat this like a minor inconvenience. Time to treat it like the emergency it is.

Stacy here

December 9, 2025 AT 06:12They’re hiding the truth. Big Pharma bought the FDA. The real shortage? The will to fix it. Why do you think every single API plant is overseas? Coincidence? Nah. It’s all about control. They want you dependent. They want you scared. They want you to beg for scraps while they profit off your panic. Wake up.

Ryan Sullivan

December 9, 2025 AT 14:55Let’s deconstruct this with empirical rigor. The marginal cost curve for generic pharmaceuticals has been structurally compressed since the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act, which mandated price benchmarking against the lowest available acquisition cost. This created a race-to-the-bottom incentive structure wherein capital allocation is systematically diverted from redundancy, quality assurance, and supply chain diversification. The result is a fragile, monolithic, and economically unsustainable production ecosystem. The FDA’s role is regulatory, not fiscal. Blaming them is a category error.

Wesley Phillips

December 9, 2025 AT 20:59Olivia Hand

December 11, 2025 AT 15:21I’ve been tracking this since 2021. The FDA’s public dashboard shows a 217% increase in critical drug shortages since 2019-but the real metric is the number of patients who’ve had to delay treatment. I’ve interviewed 37 oncology nurses. Every single one said they’ve had to tell someone, "We don’t have it." No one’s counting those stories. That’s the real data.

Desmond Khoo

December 12, 2025 AT 19:27Bro. This is wild. 😢 I just got off the phone with my grandma’s pharmacy-she’s on insulin. They said "we’re good for now, but next week? No guarantees." I’m gonna start a GoFundMe for her meds. But seriously-why is this still happening? We have the tech. We have the money. We just don’t care enough. 🙏 #FixTheSystem

Louis Llaine

December 13, 2025 AT 07:09So let me get this straight-we spend $1.2 trillion on healthcare, but can’t afford to make a $0.90 vial? Wow. The real drug shortage is common sense. Next up: we’ll be rationing oxygen because it’s "too expensive to produce in bulk."

Jane Quitain

December 14, 2025 AT 15:53my mom got her chemo delayed last week and i just cried in the parking lot. we need to do better. i dont know how but we gotta try. please someone help. this is not right.

Kyle Oksten

December 15, 2025 AT 00:27What’s being ignored is the moral architecture of this system. We’ve outsourced not just manufacturing, but responsibility. We treat medicine as a commodity, not a right. And when we do, we normalize suffering as collateral. This isn’t policy failure-it’s ethical collapse. We can fix the supply chain. But first, we have to decide what kind of society we want to be.

Jennifer Anderson

December 15, 2025 AT 17:49hey if you’re reading this and you’re scared-i got you. i’ve been there. i called 12 pharmacies before finding my kid’s antibiotic. it’s not your fault. we’re all just trying to survive a broken system. but we’re not alone. join the advocacy groups. talk to your rep. we can change this. together.