Generic Myths Debunked: Separating Fact from Fiction in Patient Education

How many times have you heard that you need to drink eight glasses of water a day? Or that sugar makes kids hyper? What about the idea that we only use 10% of our brains? These aren’t just harmless stories-they’re myths that shape how people make decisions about their health. And when those myths stick, they can lead to poor choices, wasted money, and even real harm.

Why Myths Stick-Even When They’re Wrong

Myths don’t survive because they’re true. They survive because they’re simple, repeated, and often tied to emotions or cultural habits. The brain prefers easy answers over complex truths. When a myth feels right-like sugar causing hyperactivity because kids get excited at birthday parties-it’s harder to let go, even when science says otherwise. A 2022 Pew Research study found that 62% of U.S. adults see misinformation online at least once a week. In healthcare, this is dangerous. Patients might skip vaccines because they believe they cause autism. They might avoid antibiotics because they think all infections are viral. Or they might spend hundreds on "superfoods" thinking they’ll cure chronic illness. The good news? Myths can be corrected. But not by shouting facts. The way you deliver the truth matters just as much as the truth itself.Myth: You Lose 70-80% of Your Body Heat Through Your Head

This one’s been around for decades. It started with a U.S. military study in the 1950s where subjects wore Arctic gear-but left their heads uncovered. Because their heads were the only exposed skin, they lost more heat there. But that doesn’t mean the head is special. The truth? Your head makes up about 7-10% of your total body surface area. So, if it’s cold and uncovered, you’ll lose roughly that much heat-no more, no less. The same goes for your hands, feet, or any other exposed part. Cover your head if you’re cold, sure. But don’t think it’s the main culprit. Wear a hat, gloves, and layers. Heat loss isn’t about one body part-it’s about exposure.Myth: You Need Eight Glasses of Water a Day

This rule pops up everywhere: on water bottles, in fitness apps, even in doctor’s offices. But there’s no scientific study that supports it. Dr. Heinz Valtin, a kidney specialist at Dartmouth, reviewed decades of research in 2002 and found zero evidence for the "eight glasses" rule. Your body gets water from food, coffee, tea, soup, fruit, and more. Hydration needs vary wildly based on climate, activity level, age, and health. One person might need 2 liters. Another might need 3.5. The best signal? Thirst. If you’re not thirsty and your urine is pale yellow, you’re likely fine. Chasing arbitrary numbers can lead to overhydration-which is just as risky as dehydration.Myth: Sugar Causes Hyperactivity in Children

Parents swear it. Teachers report it. Birthday parties are blamed for chaos. But since the 1990s, 23 double-blind studies have shown no link between sugar and hyperactivity in children. A 2021 meta-analysis in JAMA Pediatrics confirmed this: sugar doesn’t make kids more restless. So why does the myth persist? Because it’s convenient. It’s easier to blame sugar than to admit that kids are naturally energetic, or that parties are exciting environments. The sugar industry even funded research in the 1980s to muddy the waters, as documented in the Archives of Internal Medicine. When a myth serves a financial interest, it’s harder to kill.Myth: We Only Use 10% of Our Brains

This myth shows up in movies, ads, and self-help gurus promising you can unlock your "hidden potential." It’s false-and dangerously misleading. Modern brain scans (fMRI, PET) show every part of the brain has a function. Even during sleep, your brain is active. Damage to any area-no matter how "small"-can cause serious effects. The 10% myth came from a misquote of psychologist William James in the 1920s. He said we only use a fraction of our mental potential-not our physical brain. Neuroscientists at the University of Alabama at Birmingham confirmed in 2022 that there’s no unused tissue. You’re using 100% of your brain, just not all at once.

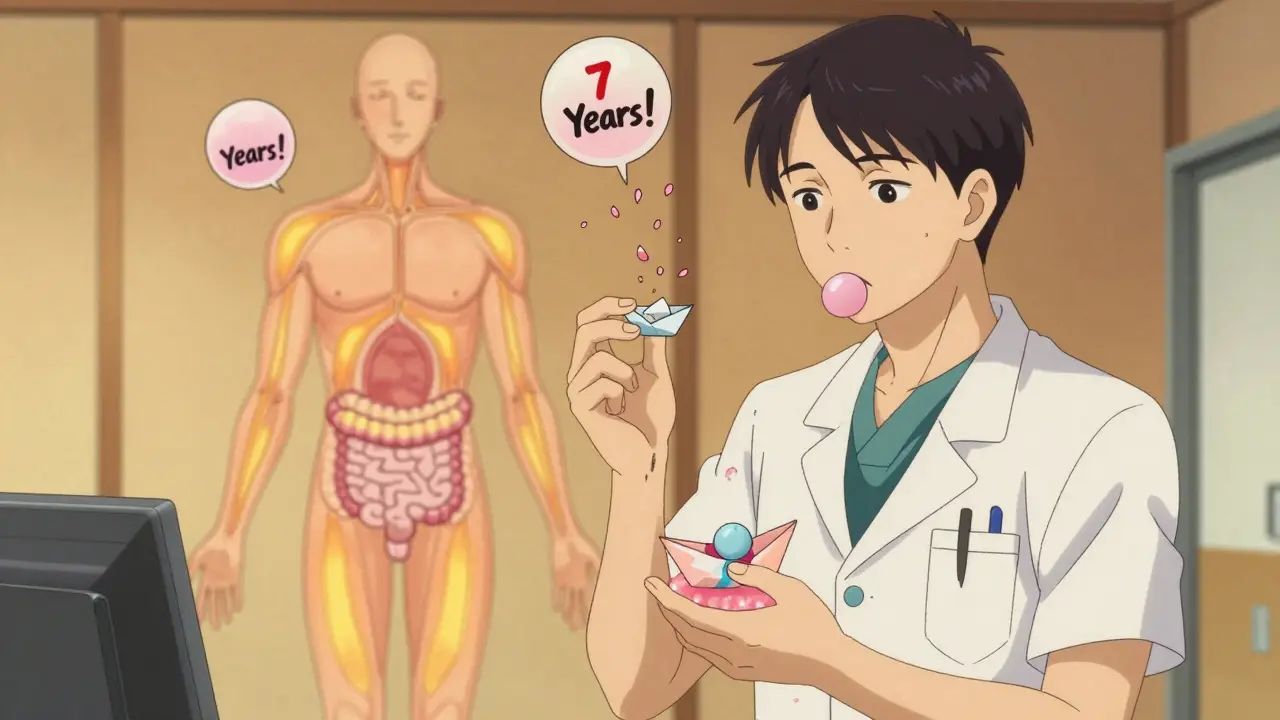

Myth: Chewing Gum Stays in Your Stomach for Seven Years

This one’s a classic parental warning. "Don’t swallow gum-it’ll stick around for years!" But it’s not true. Gum isn’t digested, yes. But it doesn’t stick to your insides. Dr. Ian Tullberg at UCHealth confirmed in 2022 that gum passes through your digestive system in 2-4 days, just like other indigestible items-like corn kernels or sesame seeds. Your gut moves things along. It doesn’t trap them. The real risk? Swallowing large amounts of gum over time, especially in young children, could cause blockages. But one piece? No problem.Myth: Superfoods Like Acai or Goji Berries Are Miracle Cures

"Superfood" isn’t a scientific term. It’s a marketing label. The European Food Information Council found no evidence that any single food-no matter how exotic-offers extraordinary health benefits beyond what a balanced diet provides. Acai berries are rich in antioxidants? So are blueberries, blackberries, and even red onions. Goji berries have vitamin A? So do carrots and sweet potatoes. You don’t need to pay $20 for a bag of dried goji berries when you can get the same nutrients for a fraction of the cost from local produce. Focusing on one "miracle" food distracts from the real goal: variety, moderation, and whole foods.How to Correct Myths Without Making Them Worse

Just saying "that’s wrong" often backfires. People double down when their beliefs are challenged-especially if those beliefs are tied to identity, culture, or emotion. Experts now recommend the "truth sandwich" method:- Start with the truth. "Your body gets water from many sources, not just eight glasses a day."

- Briefly mention the myth-with clear labeling. "Some people think you need exactly eight glasses, but that’s not based on science."

- End with the truth again. "Drink when you’re thirsty. Monitor your urine color. That’s the best guide."

What Works Best in Patient Education

Health systems that actively debunk myths see better outcomes. UCHealth’s article on chewing gum got over 1.2 million views in a month. Why? Because it was clear, relatable, and used a trusted voice. YouTube videos outperform text. Veritasium’s video on body heat loss hit 4.7 million views with 89% positive engagement. Visuals-like showing how heat escapes from skin-make abstract science concrete. The CDC’s "Myth vs. Fact" template is used by 78% of U.S. health departments. But it only works if staff are trained. A 2023 survey found it takes 12-16 hours of training to use it well. Without training, corrections feel robotic-or worse, condescending.

Why This Matters for Patients

When patients believe myths, they delay care. They avoid medications. They buy useless supplements. They refuse vaccines. They blame themselves for illnesses they didn’t cause. Correcting myths isn’t about being right. It’s about helping people make better decisions. When a parent learns sugar doesn’t cause hyperactivity, they stop feeling guilty. When someone learns they don’t need to drink eight glasses of water, they stop stressing over their daily intake. When a patient understands that chewing gum doesn’t stay in their stomach, they stop fearing small mistakes. The goal isn’t to win an argument. It’s to reduce fear, reduce confusion, and restore trust in science.What’s Changing in 2026

Technology is helping. Google’s "About This Result" feature now gives context for 87% of search results, helping people spot misinformation before they click. The WHO’s Myth Busters program has corrected over 2,300 health myths across 187 countries-cutting vaccine hesitancy by 22% in those areas. New AI tools like MIT’s "TruthGuard" can now predict emerging myths with 83% accuracy by spotting patterns in social media language. And by 2024, fact-checkers will be certified through the International Fact-Checking Network, raising the bar for quality. But the biggest change? More hospitals are training staff to talk about myths-not just treat symptoms. In 2020, only 12 U.S. hospitals had formal myth-debunking protocols. By 2023, that number jumped to 68. Patients who hear myths addressed directly are 31% more likely to follow medical advice.What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a degree to help fight misinformation. Here’s how:- When someone says "I heard sugar makes kids hyper," say: "Actually, 23 studies have looked into this. Sugar doesn’t cause hyperactivity. It’s the excitement of the party, not the candy."

- Don’t share unverified health posts. If you’re unsure, wait. Check with a trusted source like the CDC, WHO, or a medical journal.

- Ask your doctor: "Is there a common myth about this condition I should know about?"

- Teach kids early. "Gum doesn’t stick in your tummy. It just passes through."

Are all health myths harmful?

Not all are dangerous, but many are. Myths like "you need eight glasses of water" are mostly harmless inconveniences. But myths like "vaccines cause autism" or "antibiotics cure viruses" can lead to serious health risks. The harm depends on whether the myth affects medical decisions. When people avoid treatment, delay care, or take unsafe supplements because of a myth-that’s when it becomes dangerous.

Why do people believe myths even when they’re proven wrong?

Beliefs are tied to identity, emotion, and social groups. If your family always said sugar causes hyperactivity, admitting it’s false can feel like rejecting your upbringing. People also trust stories more than data. A personal anecdote-"My cousin ate sugar and went wild"-feels more real than a 23-study meta-analysis. Plus, myths are often repeated by influencers, ads, or social media, making them feel true by sheer volume.

Can I debunk myths on social media without causing backlash?

Yes, but tone matters. Avoid saying "You’re wrong." Instead, say "I used to believe that too, until I saw the research." Share a short, clear fact with a credible source. Use the truth sandwich: state the fact, name the myth, restate the fact. People are more open when they don’t feel attacked. And never argue with someone who’s emotionally invested-redirect to a trusted link instead.

Do supplements labeled as "superfoods" actually work better than regular foods?

No. There’s no scientific definition for "superfood." Acai, goji berries, chia seeds, and kale are nutritious, but so are apples, spinach, beans, and brown rice. The difference is price, not power. You get the same antioxidants, fiber, and vitamins from local, seasonal foods. Paying extra for exotic imports doesn’t improve your health-it just improves someone else’s profit margin.

How do I know if a source is trustworthy for debunking myths?

Look for sources that cite peer-reviewed studies, name researchers or institutions, and update their content. Trusted sources include the CDC, WHO, Mayo Clinic, Cochrane Collaboration, and university medical centers. Avoid blogs, Instagram influencers, or sites selling products. If a source says "scientists say" without naming who or citing research, it’s not reliable.

Is it true that fact-checking can sometimes make myths stronger?

Yes-this is called the "backfire effect." If you repeat a myth without clearly labeling it as false, people might remember the myth but forget the correction. That’s why experts use the truth sandwich: state the truth first, mention the myth briefly with a clear "this is false" label, then repeat the truth. Avoid repeating the myth too much. Less repetition = less reinforcement.

sagar sanadi

January 20, 2026 AT 09:49Oh wow, so now the government wants us to believe we’re not supposed to drink 8 glasses of water? Next they’ll say the moon landing was real and sugar doesn’t make kids hyper because the CIA planted the idea to sell more soda. 😏

I’ve seen people drink 20 glasses a day and still get sick. Coincidence? I think not. They’re hiding the truth. The real enemy is the water corporations who want you to think you’re hydrated when you’re actually being programmed by the hydration agenda.

And don’t get me started on the 10% brain myth. That’s not a myth-that’s a cover-up. They don’t want you to know you could be using 90% if you just stopped watching TikTok and started listening to the right podcasts. I heard a guy on YouTube who said the brain is just a receiver-and the real power is in the ion clouds above Antarctica. Science? Pfft.

kumar kc

January 20, 2026 AT 22:31Stop spreading misinformation. Sugar doesn’t cause hyperactivity. End of story.

Emily Leigh

January 21, 2026 AT 19:37Okay but… why do we even care so much about debunking myths? Like, is it really that harmful if someone thinks chewing gum stays in their stomach for seven years? I mean, it’s not like they’re going to stop eating gum… it’s just a fun little superstition. Like believing in lucky socks or that your phone is spying on you because you just talked about tacos…

Also, the ‘truth sandwich’? That sounds like something a corporate wellness coach would make for a team-building retreat. ‘Here’s your truth, here’s your myth, here’s your truth again-now go hydrate and believe in the system.’

Meanwhile, I’m just over here drinking kombucha and wondering if the ‘superfood’ label is just capitalism’s way of selling us the same berries at 10x the price with glitter on the bag.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘we only use 10% of our brains’ thing… I mean, I’m pretty sure I use like 12% on a good day. The rest? Napping.

Also, why does everything have to be so… clinical? Can’t we just enjoy the mystery? Maybe the brain is a quantum computer and we’re all just beta testers. Who’s to say?

…I’m just saying. Maybe the myth is the point.

Renee Stringer

January 23, 2026 AT 07:13I appreciate the effort to correct misinformation, but the tone of this piece feels overly clinical. People don’t respond to facts alone-they respond to trust. If you don’t build that first, none of this matters.

And the ‘truth sandwich’ method? It’s not enough. You have to show up consistently. One article won’t undo decades of propaganda. It’s a drip, not a flood.

Also, calling something a ‘myth’ can feel like an insult. Maybe instead of ‘debunking,’ we should say, ‘here’s what we’ve learned since then.’ Less adversarial. More human.

Shane McGriff

January 23, 2026 AT 16:16Really glad someone wrote this. I’ve had parents come to me crying because they think their kid’s ADHD is just ‘too much sugar.’ They feel guilty. Like they’re bad parents because their child ran wild at a birthday party.

And then there’s the guy who refused antibiotics because he ‘heard they cause autism.’ He ended up with sepsis. We saved his life-but he still believes it.

It’s not about being right. It’s about being kind enough to meet people where they are. That’s why I always start with, ‘I used to believe that too.’ It opens the door.

And yeah, the ‘eight glasses’ thing? I tell my patients: if your pee looks like lemonade, you’re good. If it looks like apple juice? Drink more. If it looks like tea? You’re probably fine. No math needed.

Truth is, most people just want to feel like they’re doing the right thing. Give them a simple, calm way to do that-and they’ll follow.

pragya mishra

January 24, 2026 AT 08:49Wait, so you’re telling me I don’t need to buy $50 bags of goji berries? But my yoga instructor said they’re the only way to detox my chakras! And she’s got 200K followers! You’re just a doctor, you don’t know anything about energy fields!

Also, why are you so sure about the brain thing? What if the 90% is in the spiritual dimension? I’ve read about it on a blog by a guy who channeled Einstein. He said the brain is a satellite dish for the collective consciousness. And your article is just a distraction from the truth.

And what about the water? I drink 12 glasses and I feel ‘cleansed.’ If science says it’s not necessary, then science is wrong. My body knows better.

Also, your article didn’t mention the 5G towers that are secretly controlling our hydration levels. I’ve seen the videos.

Andy Thompson

January 25, 2026 AT 18:52USA is being manipulated. The WHO? The CDC? All owned by globalists who want to control your water intake and brain usage. You think sugar doesn’t cause hyperactivity? HA. Look at the schools-kids are zoned out after lunch. That’s not normal. That’s chemtrails in the juice boxes.

And don’t get me started on the ‘truth sandwich.’ That’s just the elite’s way of making you think you’re being educated while they feed you lies through a fork. They want you to believe in ‘science’ so you don’t question the vaccines, the water fluoridation, or the fact that your phone is listening to you right now.

They’re scared you’ll find out the truth. That’s why they write articles like this. But I see through it. I’ve got 17 YouTube channels that prove all this. You think I’m paranoid? No. I’m informed.

And if you think I’m gonna stop drinking my 12 glasses of alkaline water with Himalayan salt? You’re dreaming. 😎

Thomas Varner

January 26, 2026 AT 23:35Man… I read this whole thing and just sat there nodding like a bobblehead.

It’s wild how much we just… accept stuff. Like, I used to think gum stayed in your stomach for seven years. I told my niece that. She believed it. Now I feel bad.

And the eight glasses thing? I’ve been tracking my water for years. I drink when I’m thirsty. Sometimes it’s 3 cups. Sometimes it’s 6. I don’t stress. My pee is pale yellow. I’m fine.

Also, superfoods? I bought a $30 bag of acai powder last year. It sat in my cupboard for 11 months. I ended up using it as a coffee stirrer. It didn’t cure my arthritis. But it did make my coffee look cool.

Maybe the real myth is that we need a myth to feel like we’re doing something right. Sometimes… just being okay is enough.