Hypocalcemia in Critical Care: Diagnosis and Management Guide

Hypocalcemia Calculator

Calculate Adjusted Calcium

Enter clinical values to calculate albumin-adjusted calcium levels

Quick Summary

- Identify hypocalcemia early with ionized calcium, not total calcium alone.

- Check albumin, magnesium and vitamin D levels to uncover hidden causes.

- Treat symptomatic patients promptly with calcium gluconate or calcium chloride.

- Correct underlying drivers - sepsis, renal failure, or medication effects - to prevent recurrence.

- Monitor ECG changes and repeat labs every 4‑6hours until stable.

In the ICU, low calcium can hide behind many critical illnesses. This guide walks you through spotting it, figuring out why it’s happening, and safely correcting it.

When the body’s calcium drops below normal, the heart, nerves and muscles can misbehave. In a hypocalcemia is a condition where serum calcium levels fall below the reference range, often defined as total calcium <8.5mg/dL or ionized calcium <1.0mmol/L, the stakes are high for ventilated patients, post‑operative patients, and those with severe sepsis.

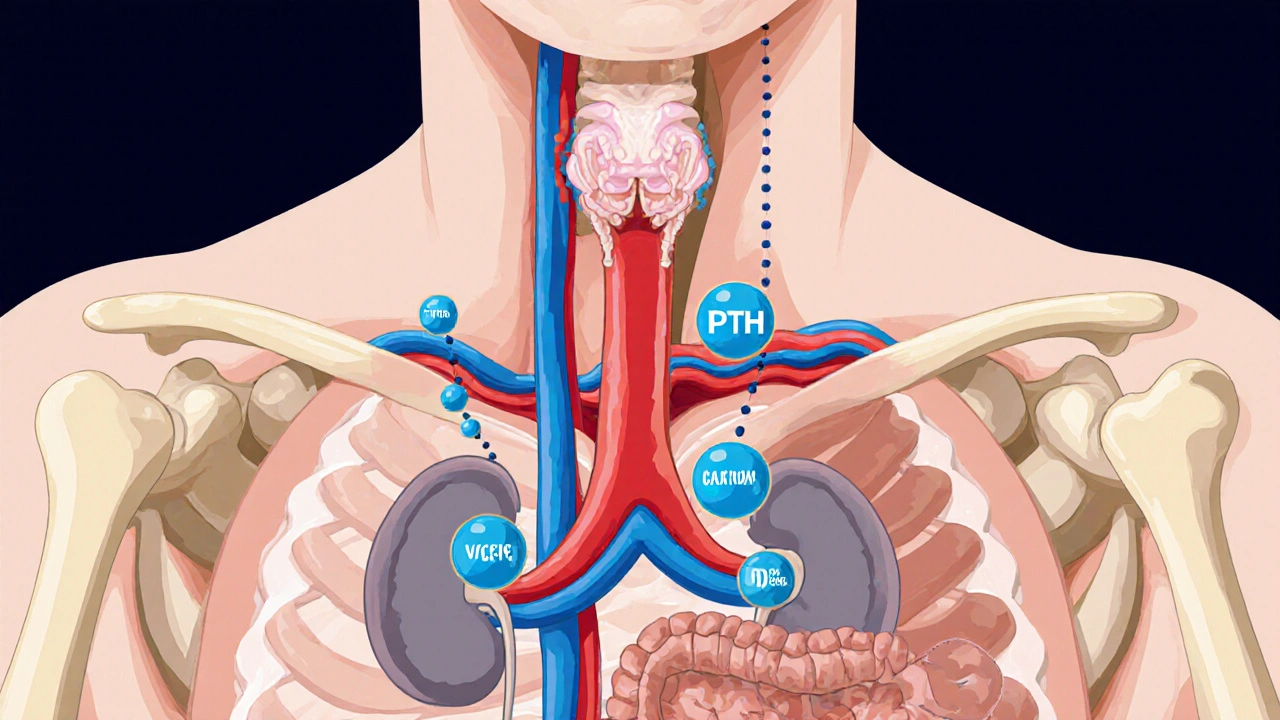

Understanding Calcium Physiology in the ICU

Calcium exists in two main forms in blood: bound to proteins (mostly albumin) and free (ionized) calcium, which does the real work. Only the ionized fraction triggers muscle contraction, hormone release, and blood clotting.

Key regulators include parathyroid hormone (PTH), which raises calcium by increasing bone release, kidney reabsorption, and vitamin D activation, and vitamin D, which enhances intestinal absorption.

In critical illness, these pathways can be blunted, while factors like massive transfusion, citrate load, and hypo‑magnesemia tug calcium down.

Step‑by‑Step Diagnosis

- Measure ionized calcium first. Total calcium can be misleading if albumin is low, a common scenario in sepsis or after massive fluid resuscitation.

- Check magnesium levels. Magnesium deficiency impairs PTH secretion and worsens hypocalcemia.

- Order a basic metabolic panel to assess renal function, as chronic kidney disease reduces vitamin D activation.

- Screen for vitamin D deficiency, especially in patients with limited sunlight exposure or malnutrition.

- Review medication list for citrate‑containing blood products, loop diuretics, bisphosphonates, or proton‑pump inhibitors.

- Obtain a 12‑lead electrocardiogram (ECG). Look for a prolonged QT interval, flattened T‑waves, or a U‑wave, classic signs of low calcium.

- If the cause remains unclear, consider measuring albumin and calculate corrected calcium, but remember ionized calcium is still the gold standard.

Common ICU Triggers - Quick Reference Table

| Cause | Ionized Ca (mmol/L) | Mg (mmol/L) | PTH | Vitamin D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis‑associated cytokine storm | 0.8‑0.9 | 0.6‑0.8 (low) | inappropriately low or normal | often low |

| Massive transfusion (citrate load) | 0.9‑1.0 | normal | normal | normal |

| Renal failure | 0.8‑1.0 | low‑normal | elevated | low (1,25‑OH) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 0.7‑0.9 | <1.5 | suppressed | normal |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 0.8‑0.95 | normal | elevated | low |

Management Overview

Therapy splits into two streams: rapid correction for symptoms and longer‑term correction of the underlying deficit.

When to Act Quickly

- Severe symptomatic hypocalcemia (ionized Ca<0.9mmol/L) with tetany, seizures, or life‑threatening arrhythmias.

- ECG shows QT prolongation >460ms or ominous ventricular ectopy.

Give a bolus of calcium gluconate 10mL of 10% solution (≈90mg elemental calcium) intravenously over 5‑10minutes. In patients with central line access and no peripheral vein irritation concerns, calcium chloride 10mL of 10% (≈300mg elemental calcium) provides a stronger dose but can cause tissue necrosis if extravasated.

After the bolus, start a continuous infusion: calcium gluconate 1-2mg/kg/hr of elemental calcium, titrated to keep ionized calcium >1.0mmol/L and ECG stable.

Correcting the Root Cause

- Magnesium repletion: Give 1‑2g magnesium sulfate IV over 1hour, then 0.5‑1g/hr as needed.

- Vitamin D supplementation: Load with 300,000IU cholecalciferol orally or via nasogastric tube, then maintain 1000‑2000IU daily.

- Renal replacement therapy: Adjust calcium dialysate concentration if the patient is on CRRT.

- Medication review: Stop or dose‑adjust citrate‑containing blood products, loop diuretics, or bisphosphonates until calcium stabilizes.

- Nutrition: Provide enteral or parenteral formulas enriched with calcium (1300‑1500mg/day) and vitamin D.

Special Populations

Post‑cardiac surgery patients often develop hypocalcemia due to hypoparathyroidism after gland manipulation. Target ionized calcium 1.2‑1.3mmol/L for the first 48hours.

Pregnant women in ICU need calcium goals adjusted for fetal demand. Aim for ionized calcium ≥1.1mmol/L and supplement with 500mg elemental calcium orally if tolerable.

Monitoring and Safety Checks

After the initial bolus, repeat ionized calcium and magnesium every 4hours for the next 24hours. Adjust infusion rates based on trends.

Watch the ECG continuously for QT interval normalization. In patients with existing cardiac disease, a rapid rise in calcium can provoke Brugada‑type patterns, so increase slowly.

Check serum phosphate daily - hypocalcemia can coexist with hyperphosphatemia in renal failure, and aggressive calcium may precipitate calcium‑phosphate crystals.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Relying on total calcium alone in hypo‑albuminemic patients - you’ll miss up to 30% of cases.

- Neglecting magnesium - low magnesium disables PTH and can cause refractory hypocalcemia.

- Overshooting calcium - hypercalcemia can cause arrhythmias, renal vasoconstriction, and mental status changes.

- Forgetting to adjust calcium in CRRT - the dialysate calcium concentration must match patient needs.

- Skipping vitamin D assessment - without adequate 25‑OH and 1,25‑OH levels, calcium replacement is a Band‑Aid.

Practical Checklist for ICU Teams

- Draw ionized calcium, magnesium, phosphate, albumin, PTH, and 25‑OH vitamin D on admission.

- Obtain a baseline ECG.

- If ionized Ca<0.9mmol/L+symptoms, give calcium gluconate bolus.

- Start calcium infusion and set target ionized Ca>1.0mmol/L.

- Replace magnesium if <0.7mmol/L.

- Correct vitamin D deficiency within 48hours.

- Re‑measure labs q4‑6h, adjust infusion, and document ECG changes.

- Review all calcium‑affecting meds daily.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is ionized calcium preferred over total calcium in the ICU?

Total calcium binds to albumin, and critical patients often have low albumin due to inflammation or fluid shifts. Ionized calcium measures the physiologically active fraction directly, giving a reliable picture regardless of albumin levels.

How fast can calcium gluconate raise ionized calcium?

A 10mL bolus of 10% calcium gluconate typically raises ionized calcium by 0.2‑0.3mmol/L within 5‑10minutes, enough to relieve severe tetany or arrhythmia.

Can hypomagnesemia cause hypocalcemia even if calcium looks normal?

Yes. Magnesium is required for PTH release and for the kidneys to reabsorb calcium. Low magnesium can blunt the PTH response, leading to a hidden calcium deficit that only surfaces after magnesium is corrected.

When should calcium chloride be used instead of calcium gluconate?

Calcium chloride delivers about three times more elemental calcium per milliliter, so it’s chosen for rapid, life‑threatening hypocalcemia when central venous access is secure. It should be avoided in peripheral lines due to risk of tissue necrosis.

What ECG changes are most indicative of hypocalcemia?

A prolonged QT interval (>460ms), flattened or inverted T‑waves, and a prominent U‑wave are classic. These changes improve as calcium normalizes.

Sherine Mary

October 13, 2025 AT 12:25The calculator is a useful bedside tool, but clinicians must remember that ionized calcium remains the gold standard in the ICU. Relying on albumin‑adjusted totals can mask severe hypocalcemia, especially when albumin is rapidly shifting. Moreover, the guide could benefit from a clear algorithm for when to switch to calcium gluconate versus calcium chloride.

AARON KEYS

October 17, 2025 AT 03:25I appreciate the concise summary; it captures the essentials without overwhelming the reader. The bullet points are well‑structured, and the reminder about ECG monitoring is spot on. Perhaps a brief note on dosing adjustments in renal failure would make it even more comprehensive.

Summer Medina

October 20, 2025 AT 18:25Honestly this guide looks kinda slick but let me tell u why it’s missing the mark you see the thing about ionized calcium is key and yet the page spends forever on total calcium its like they dont get the urgency of sepsis u know when patients are on massive transfusion protocols the citrate load drains calcium fast so you gotta check ionized immediately also the magnesium part is barely mentioned which is a huge oversight cuz low mg messes up pth release and makes calcium therapy less effective plus the whole adjusted calcium formula is just a rough estimate not a substitute for real lab values

Melissa Shore

October 24, 2025 AT 09:25The guide is thorough and user‑friendly it walks through the steps without unnecessary jargon it also highlights the importance of checking albumin and magnesium levels which many resources omit it reminds us to monitor ECG changes and repeat labs regularly this systematic approach can really help reduce errors in the ICU

Michelle Pellin

October 27, 2025 AT 23:25The section on magnesium assessment is a commendable inclusion, as hypomagnesemia often coexists with hypocalcemia.

Clinicians frequently overlook the synergistic effect of low magnesium on parathyroid hormone release.

By correcting magnesium first, subsequent calcium repletion becomes more effective.

The guide rightly emphasizes ECG monitoring, yet it could expand on specific arrhythmic patterns to watch for.

For instance, prolonged QT interval is a classic manifestation that can precipitate torsades.

In practice, serial ECGs every four hours may be burdensome, but they are justified in unstable patients.

The dosage tables for calcium gluconate and calcium chloride are clear, though a reminder about peripheral venous irritation would be prudent.

Importantly, the recommendation to use ion‑selective electrodes for ionized calcium aligns with current best practices.

The guide could also address the impact of citrate anticoagulation in CRRT on calcium levels.

Patients on massive transfusion protocols often develop hypocalcemia due to citrate load, a nuance worth highlighting.

A brief discussion on vitamin D status would round out the differential diagnosis, since deficiency can blunt calcium recovery.

Similarly, chronic kidney disease introduces complex mineral bone disorders that modify calcium handling.

The flowchart at the end provides a helpful visual, but color‑coding it for severity would enhance usability.

Overall, the resource balances brevity with depth, making it suitable for rapid reference on the ward.

Future revisions might incorporate a mobile app version to streamline calculations at the bedside.

Keiber Marquez

October 31, 2025 AT 14:25Nice work.

Lily Saeli

November 4, 2025 AT 05:25From an ethical standpoint, overlooking ionized calcium measurements in critical patients is a disservice to the vulnerable. The guide should stress that safeguarding life requires the most accurate tools, not convenient shortcuts. Anything less borders on negligence.

April Conley

November 7, 2025 AT 20:25As a cultural ambassador I note that hypocalcemia management protocols vary worldwide; many regions rely on different reference ranges. It would be valuable to include a note on local laboratory standards to avoid misinterpretation across borders.

Sophie Rabey

November 11, 2025 AT 11:25Oh great, another calculator-because we all have time to pause the code in the middle of a code blue to click a button. But seriously, the extra step of adjusting for albumin is better than nothing, even if it feels a bit like we’re doing math instead of saving lives.

Sean Powell

November 15, 2025 AT 02:25Hey team, this guide is a solid start! I’d love to see a quick‑reference table for calcium dosing in pediatric patients too. Also, consider adding a short video demo for the calculator-makes onboarding easier for new staff.

Isha Khullar

November 18, 2025 AT 17:25It is profoundly disheartening to witness a medical resource that skirts the gravity of electrolyte imbalance. Hypocalcemia is not merely a lab value; it is a silent predator that can cripple the heart, the nerves, the very essence of human vitality. To treat it half‑heartedly is to betray the oath we took.

jeff lamore

November 22, 2025 AT 08:25I respect the effort put into this summary. It remains fairly balanced and avoids overly technical language, which is helpful for interdisciplinary teams. A minor suggestion: perhaps include a disclaimer about the calculator’s limitations.

Kris cree9

November 25, 2025 AT 23:25The guide is decent but could use more depth.

Ian McKay

November 29, 2025 AT 14:25While the content is generally accurate, there are a few grammatical oversights that could be refined for professional presentation.

Deborah Messick

December 3, 2025 AT 05:25Contrary to the optimistic tone of many such resources, one must acknowledge that hypocalcemia management remains fraught with uncertainties, particularly regarding optimal target ranges in diverse patient populations.

Jolanda Julyan

December 6, 2025 AT 20:25I appreciate the collaborative spirit of this guide; the step‑by‑step layout fosters team cohesion. However, the language could be more assertive when urging rapid intervention, especially in septic patients where delays are costly. Let’s ensure the tone matches the urgency of the clinical scenario.

Kevin Huston

December 10, 2025 AT 11:25This guide hits the mark on many fronts-clear layout, practical dosing tables, and a solid reminder about magnesium. Yet, it glosses over the geopolitical implications of resource allocation; many hospitals lack ready access to ionized calcium analyzers, forcing reliance on imperfect surrogates. The authors should address how clinicians can adapt protocols in low‑resource settings without compromising patient safety. Moreover, a brief critique of the over‑reliance on calcium chloride in patients with compromised vascular access would add nuance. Overall, it’s a valuable tool, but a dash of realism about global disparities would make it truly comprehensive.