Hypoglycemia in Older Adults: Special Risks and Prevention Plans

Diabetes Medication Risk Calculator for Older Adults

How This Tool Works

This tool helps you assess hypoglycemia risk of different diabetes medications specifically for older adults. Based on current medical guidelines, it shows:

- Relative risk compared to safer alternatives

- Recommendations for medication adjustment

- Key considerations for older adults

Medication Information

Insulin

High RiskLong-acting insulin types can cause dangerous lows if meals are skipped or activity levels change. Older adults often eat irregularly or have reduced appetite, increasing risk. Adjustments are crucial for safety.

Consider reducing dose or switching to shorter-acting insulin. The goal is to balance safety and blood sugar control. One study showed reducing insulin from 40 units to 20 units stopped weekly lows while maintaining A1c at 7.8%.

Sulfonylureas (e.g., Glyburide)

Medium-High RiskGlyburide has a long duration (up to days), increasing severe hypoglycemia risk by 50% compared to shorter-acting alternatives like glipizide. It's considered "potentially inappropriate medication" for seniors by American Geriatrics Society.

Consider switching to safer alternatives like glipizide or other non-hypoglycemia risk medications. One case study showed switching from glyburide reduced severe hypoglycemia events by 70%.

Other Medications (Metformin, GLP-1, SGLT2 inhibitors)

Low RiskThese medications carry very little risk of hypoglycemia when used alone. They're recommended as safer alternatives for older adults with diabetes.

These are preferred choices for older adults. Consider switching from insulin or sulfonylureas to these safer options whenever possible.

Personalized Recommendations

Key Recommendations for Older Adults

- Consider individualized A1c targets: under 7.0% for healthy seniors, under 8.0% for those with multiple conditions, under 8.5% for frail seniors

- Switch from glyburide to safer alternatives like glipizide or non-hypoglycemia risk medications

- Review insulin doses to avoid unnecessary lows

- Use continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) for early warning

- Keep glucagon kits readily available

Remember: A stable blood sugar of 150 mg/dL is safer than a risky 90 mg/dL for older adults. Safety over perfection.

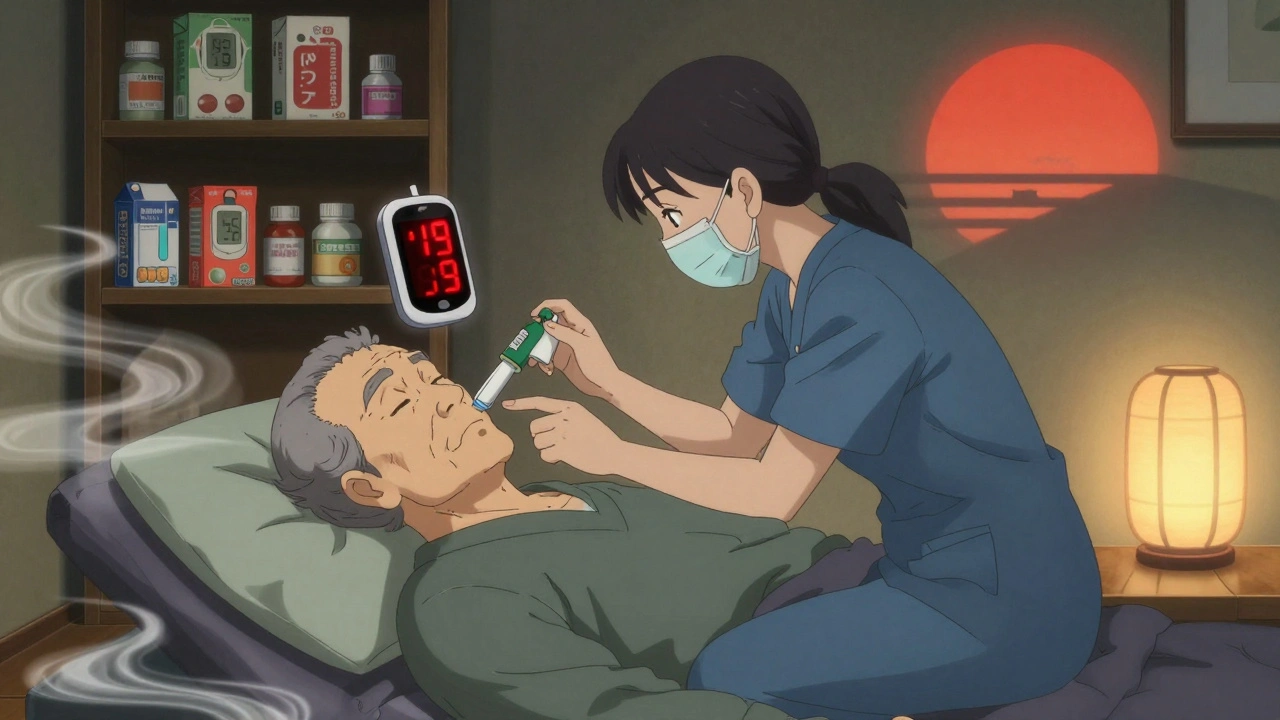

When blood sugar drops below 70 mg/dL, it’s called hypoglycemia. For most people, that means sweating, shaking, or a sudden feeling of hunger. But for older adults with diabetes, it often looks nothing like that. Instead, they might get confused, stumble, or act strangely-symptoms that get mistaken for dementia, a stroke, or just aging. And that’s exactly why it’s so dangerous.

Why Older Adults Are at Higher Risk

Older adults don’t just have diabetes-they often have multiple other health problems. Kidney trouble. Heart disease. Memory loss. And they’re usually taking five or more medications. That’s the perfect setup for low blood sugar. One study found older adults have 2.3 times more hypoglycemic episodes than younger people with diabetes. Why? Their bodies don’t respond the same way.When blood sugar drops, healthy people release adrenaline and glucagon to raise it back up. But in older adults, those signals are blunted-sometimes by 30% to 50%. That means their body doesn’t sound the alarm until it’s too late. By the time they feel dizzy or weak, their blood sugar might already be below 50 mg/dL. And because they’ve lost the warning signs, they don’t know they’re low until they’re already in trouble.

Up to 60% of hypoglycemic episodes in seniors go unnoticed or unreported. Caregivers often don’t realize what’s happening until the person collapses, falls, or becomes unresponsive. That’s not just scary-it’s deadly. Each low blood sugar episode increases the risk of a fall by 40%, a hip fracture by 25%, and a heart event by 30%.

The Medications That Put Seniors at Risk

Not all diabetes drugs are created equal when it comes to hypoglycemia. Some are much safer than others for older adults.Insulin and sulfonylureas are the biggest culprits. Sulfonylureas like glyburide stay active in the body for hours-even days. That’s why the American Geriatrics Society calls glyburide a potentially inappropriate medication for seniors. Studies show it increases the risk of severe hypoglycemia by 50% compared to glipizide, a shorter-acting alternative.

Insulin, especially long-acting types, can also cause dangerous lows if meals are skipped or activity levels change. Many older adults eat irregularly. They might forget to eat, or their appetite fades. That’s when insulin has nothing to work against-and blood sugar plummets.

Metformin, GLP-1 agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, and DPP-4 inhibitors carry very little risk of hypoglycemia on their own. That’s why experts now recommend switching older patients off sulfonylureas and toward these safer options whenever possible. One case from a primary care clinic showed reducing insulin from 40 units to 20 units stopped weekly lows-and kept A1c at a safe 7.8%.

What Hypoglycemia Looks Like in Seniors

Don’t expect trembling hands or cold sweat. In older adults, hypoglycemia often shows up as:- Sudden confusion or disorientation

- Slurred speech

- Agitation or unusual behavior

- Dizziness or unsteadiness

- Weakness or fatigue

- Loss of consciousness

One caregiver on a diabetes forum described her 82-year-old father with dementia: “He doesn’t say he’s low. He just stares blankly. By the time I check his meter, it’s below 40.” That’s not unusual. Nearly 72% of older adults say they don’t feel symptoms until their blood sugar is already dangerously low.

And if they have cognitive decline? That’s a double threat. They can’t recognize the symptoms. They can’t tell someone. They might even refuse to eat when they’re low because they don’t understand why. This is why hypoglycemia is one of the leading causes of new cognitive decline in seniors with diabetes-studies show a 1.8 times higher risk over just two years.

Prevention Starts With a Personalized Plan

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution. A healthy 70-year-old who walks daily and eats regularly needs different goals than an 85-year-old with heart failure, kidney disease, and dementia.The American Diabetes Association now recommends individualized A1c targets:

- Healthy, active seniors: under 7.0%

- Those with multiple chronic conditions: under 8.0%

- Frail or with limited life expectancy: under 8.5%

That’s a big shift from the old “lower is better” mindset. Tight control doesn’t save lives in older adults-it puts them at risk. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s safety.

One successful program in Pennsylvania, the Pottstown Primary Care Intervention, showed that just three clinic visits over six months-focused on reviewing meds, adjusting goals, and checking for hypoglycemia history-cut the number of seniors at high risk by 46%. A1c barely changed. But the number of lows dropped sharply.

Tools That Help: CGM and Glucagon

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) like the Dexcom G7 or Abbott FreeStyle Libre 3 are game-changers. They show real-time trends, alert you to drops before they happen, and can even predict lows. But only about 15% of older adults use them-mostly because of cost and lack of provider training.Medicare now covers CGMs, but only for people on insulin. That leaves out many seniors on sulfonylureas who are just as vulnerable. That’s a gap that needs fixing.

Glucagon is another lifesaver. The new nasal glucagon (Baqsimi) is easy to use-no injection, no mixing. Just spray it in the nose. One caregiver said it saved her mother’s life when she couldn’t swallow juice during a severe low. Every older adult on insulin or sulfonylureas should have a glucagon kit-and their caregiver should know how to use it.

What Caregivers and Families Can Do

You don’t need to be a doctor to help. Here’s what works:- Keep a log of low blood sugar events-when they happened, what the person was doing, what meds they took.

- Make sure meals are regular and easy to eat. Snacks like granola bars, juice boxes, or glucose tablets should be visible and accessible.

- Check blood sugar before bed, before driving, and after physical activity-even if the person says they’re fine.

- Teach everyone in the household how to recognize non-classic symptoms: confusion, slurring, stumbling.

- Make sure glucagon is stocked, not expired, and stored where it’s easy to grab.

- Ask the doctor: “Is this medication still necessary? Could we switch to something safer?”

Many older adults are afraid to reduce their meds. They think lower blood sugar means better control. But the truth? A stable 150 mg/dL is safer than a risky 90 mg/dL.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Hypoglycemia isn’t just a medical event. It’s a turning point. After one severe low, many seniors lose their independence. They stop driving. They fall and break a hip. They end up in rehab-or worse, in a nursing home. One study found that older adults who had a severe hypoglycemic episode were 2.5 times more likely to die within five years.And the costs? Each emergency visit for a severe low averages $1,200. In the U.S., hypoglycemia sends 100,000 older adults to the ER every year. That’s $120 million in avoidable costs-and that’s not even counting long-term care.

As the population ages, this problem will only grow. By 2040, over 80 million Americans will be 65 or older. And nearly one in four will have diabetes. We can’t afford to treat hypoglycemia as a minor side effect. It’s a major threat to health, independence, and survival.

Final Thought: Safety Over Perfection

Diabetes care for older adults isn’t about hitting perfect numbers. It’s about keeping people safe, mobile, and able to enjoy their lives. That means choosing medications wisely, setting realistic goals, and preparing for the unexpected.Ask yourself: Would you rather have a slightly higher A1c and be able to walk to the kitchen? Or a perfect number and risk falling, forgetting, or ending up in the hospital?

The answer isn’t complicated. But it requires a shift-from chasing numbers to protecting people.

Declan Flynn Fitness

December 3, 2025 AT 01:10Been there with my dad. He’d just stare at the TV like he was lost, and we thought it was dementia. Turned out his glyburide was killing him. We switched to glipizide and added a CGM - now he’s walking the dog again. 🙌

Michelle Smyth

December 3, 2025 AT 22:50How quaint. You’re treating a metabolic phenomenon as if it’s a software bug you can patch with a new prescription. The real issue is the biomedical industrial complex’s refusal to acknowledge that aging is not a pathology to be managed, but a ontological shift that pharmaceuticals were never meant to accommodate. 🤔

Patrick Smyth

December 4, 2025 AT 06:58I’m so worried about my mom. She’s 84, on insulin, and every time she gets confused, I panic. I don’t know if it’s her brain or her sugar. I checked her meter last night at 3 AM - 48. I cried. I just want her to be safe.

Louise Girvan

December 4, 2025 AT 10:32THIS is why Big Pharma wants you dead. Insulin? Sulfonylureas? They’re not drugs - they’re profit engines. The FDA is complicit. CGMs are expensive because they’re controlled by a cartel. And they don’t want you to know you can stabilize blood sugar with keto + intermittent fasting. STOP THE MEDS. START THE LIFESTYLE.

Dennis Jesuyon Balogun

December 4, 2025 AT 10:35Let me be clear - this isn’t just about glucose. It’s about dignity. When we reduce elderly care to glycemic targets, we erase personhood. A 150 mg/dL reading with a smile, a cup of tea, and a walk in the garden is worth more than a 6.8 A1c in a hospital bed. We must center humanity, not HbA1c. This post? It’s a manifesto.

Lucinda Bresnehan

December 5, 2025 AT 11:53My grandma had a Dexcom and it changed everything. She used to get so confused after lunch - we thought it was Alzheimer’s. Turns out, her lunch was too big and her insulin too strong. We cut her dose, added a snack, and now she’s baking cookies again. I’m so glad we found this. (Sorry for the typos - typing with one hand while holding her cane 😅)

Shannon Gabrielle

December 6, 2025 AT 19:33Oh wow. A whole essay on how to not kill old people with diabetes drugs. Took you 2000 words to say ‘stop giving them glyburide’? Newsflash: we’ve known this since 2012. But the docs? They’re still prescribing it like it’s a damn lottery ticket. Lazy. Complacent. Criminal.

ANN JACOBS

December 7, 2025 AT 11:50It is with profound respect for the complexity of geriatric care that I wish to emphasize the necessity of a multidimensional, patient-centered approach to hypoglycemia prevention. The physiological, psychological, and sociological dimensions of aging demand that we move beyond reductionist medical paradigms and embrace holistic, compassionate, and individually calibrated interventions that prioritize functional autonomy over arbitrary numerical benchmarks. May we all be guided by wisdom, not protocol.

Souvik Datta

December 9, 2025 AT 09:33From India to Ireland - this is the same story. My aunt in Delhi was on insulin and kept falling. Family thought she was getting weak. We checked her glucose - 39. Switched to metformin + diet. Now she dances at weddings. Don’t wait for collapse. Talk to the doctor. Ask: ‘Is this helping or hurting?’

Priyam Tomar

December 11, 2025 AT 00:43Everyone’s acting like this is new. It’s not. The ADA has known this since 2003. The problem isn’t the science - it’s that doctors don’t read. They just copy-paste protocols from 1998. And now you want to give seniors CGMs? Good luck when they can’t even turn on their TV. This is tech solutionism for people who don’t understand aging.

Jack Arscott

December 12, 2025 AT 17:28My grandpa’s glucagon kit was in the back of the cabinet. Expired. We didn’t know. 😢 Now it’s on the fridge with a big label. Everyone in the house knows how to use it. Just… please, check your supplies. It’s not just medicine - it’s love in a box. 💙

Irving Steinberg

December 14, 2025 AT 00:25So we’re supposed to just stop treating diabetes in old people? Sounds like giving up. What’s next? Let them eat cake and call it a day? I’ve seen too many people die from high sugar. Lower is better. Always. 🤷♂️

Lydia Zhang

December 14, 2025 AT 19:58Interesting. But I’m not convinced. Most seniors I know are fine. Maybe it’s just a few bad cases.

Kay Lam

December 14, 2025 AT 23:18My mother-in-law is 87. She’s on metformin and a tiny bit of insulin. We made sure she eats every three hours - oatmeal, cheese, fruit. She doesn’t have a CGM because the cost is insane. But we check her manually before bed, before meals, and after her walk. It’s not perfect, but it’s consistent. And she’s still gardening. That’s the win. No one talks about the small things that keep people alive - just the big tech fixes. But the real magic is in the routine.

Matt Dean

December 15, 2025 AT 08:08Why are we even talking about this? If you’re old and diabetic, you’re already on borrowed time. Just take your meds and stop complaining. The system works fine - it’s just not designed for you. Adapt or get out of the way.